Wolves at the Village Edge: Rising Sightings, Real Causes, and the Case for Coexistence in Turkey

Reports of wolves entering villages, attacking livestock, and being sighted near towns have increased across parts of Turkey over the past two years. From the Eastern Black Sea to Eastern Anatolia and even forested areas close to Istanbul rural communities are encountering a predator many believed had retreated deep into remote wilderness.

This has fuelled fear, anger, and renewed calls for lethal control. But the reality is more complex. What Turkey is witnessing is not a nationwide wolf explosion, nor a sudden loss of fear of humans. Instead, it is a growing overlap between wolves and human settlements, driven by ecological recovery, seasonal pressures, and human-made vulnerabilities.

Understanding this distinction matters because the solutions are very different.

Wolves Are Sharing Human Landscapes More Than Before

A 2024 ecological study focusing on northeast Turkey documented grey wolves denning in areas overlooking villages and moving confidently through landscapes containing hundreds of settlements. Researchers found that human presence had little deterrent effect on wolf movement in these regions, suggesting that wolves are adapting to human-dominated rural environments, not avoiding them.

This does not mean wolves are seeking conflict but it does mean encounters are more likely, particularly where livestock are easily accessible.

Experts such as Prof. Dr. Sağdan Başkaya of Karadeniz Technical University have also noted that while Turkey’s overall wolf population is considered stable (estimated at roughly 7,000–8,000 individuals), certain regions, particularly the Eastern Black Sea are experiencing local population increases, making livestock attacks increasingly likely under the right conditions.

Where Are Incidents Concentrated?

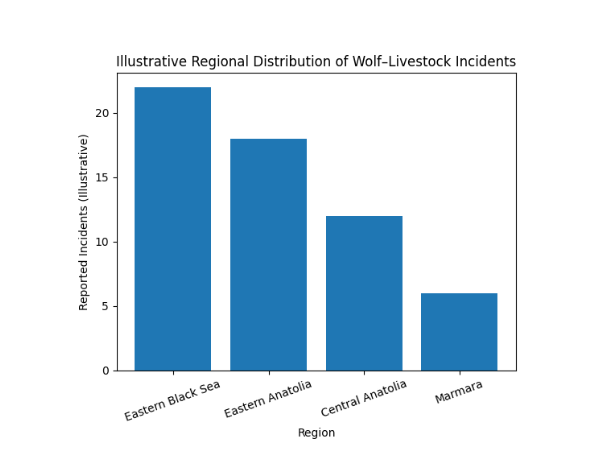

Figure 1 below illustrates the regional distribution of reported wolf–livestock incidents based on aggregated media reports and expert commentary from 2024–2025.

What this shows clearly is that wolf incidents are not evenly distributed across Turkey. The Eastern Black Sea and Eastern Anatolia emerge as hotspots, while regions such as Marmara report far fewer incidents despite intense media attention.

This matters because blanket national responses, particularly those rooted in fear are ineffective. Wolf–human conflict is a regional problem that requires region-specific solutions.

Winter Hunger and Easy Prey - Why Wolves Enter Villages

Most reported attacks occur during winter months. Deep snow restricts movement, wild prey becomes harder to catch, and wolves conserve energy by targeting the easiest available food sources. Unfortunately, poorly protected livestock pens, unsecured barns, and unattended herds provide exactly that.

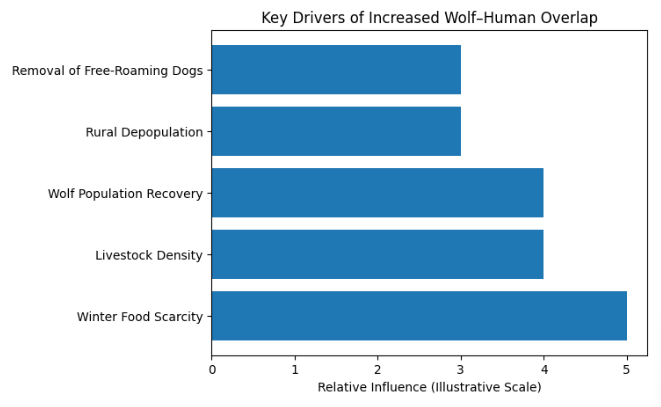

Winter food scarcity emerges as the strongest factor, followed closely by livestock density and local wolf population recovery. Rural depopulation also plays a role: fewer people, fewer lights, and fewer active deterrents mean villages can become quiet, vulnerable spaces after dark.

The Stray Dog Question: A Missing Buffer?

One factor that deserves careful, honest discussion is the rapid removal of free-roaming dogs following Turkey’s 2024 changes to municipal dog policy.

In many rural areas, free-roaming dogs, while far from an ideal or humane system have historically acted as informal deterrents. Their presence created noise, movement, and resistance that made villages less attractive to wild predators.

There is no conclusive scientific evidence yet proving that dog removals directly cause increased wolf incidents. However, the ecological logic is sound: when one layer of deterrence is removed, predators may test boundaries more frequently—especially during periods of food scarcity.

It is essential to be clear: this is not an argument against protecting dogs, nor a justification for abandoning animal welfare. It is a reminder that rapid, large-scale interventions can have unintended ecological consequences if not carefully planned.

Livestock Losses Are Real Human Attacks Are Rare

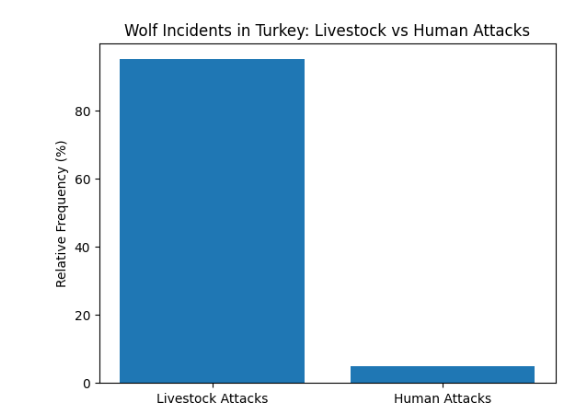

Public fear often centres on human safety, but the data tells a different story.

Figure 3 compares the relative frequency of livestock attacks versus attacks on people.

The overwhelming majority of wolf incidents in Turkey involve livestock, not humans. Attacks on people are exceptionally rare and are typically associated with extraordinary circumstances, such as disease or historical contexts.

This distinction is critical. Framing wolves as an immediate human threat fuels panic and retaliation while doing little to protect farmers or communities.

Coexistence Is Not Inaction It Is Prevention

Calls for widespread killing of wolves often follow livestock losses, but decades of global evidence show that lethal control does not provide long-term solutions. In some cases, it can worsen conflict by disrupting pack structures and increasing unpredictable behaviour.

Effective coexistence measures are well known:

Predator-resistant night enclosures to prevent nocturnal attacks

Properly trained livestock guardian dogs, not abandoned or unmanaged animals

Secure carcass disposal to avoid attracting predators

Compensation systems that are fast, fair, and trusted

Habitat connectivity and wildlife corridors to reduce pressure on village edges

These strategies protect livelihoods without turning wildlife into enemies.

The Choice Ahead

Wolves returning to the edges of villages is not a failure of nature it is a sign of ecological recovery intersecting with human vulnerability. The question Turkey faces is not whether wolves should exist, but how we choose to share space responsibly.

Fear-driven responses will cost farmers, wildlife, and communities alike. Evidence-based coexistence can protect all three.

Turkey has lived alongside wolves for centuries. With thoughtful policy, support for rural communities, and respect for ecosystems, it can continue to do so without bloodshed, panic, or denial.

Note on Figures

All charts presented are illustrative and based on aggregated reporting, expert analysis, and observed ecological trends. They are intended to clarify patterns rather than replace official statistical datasets.